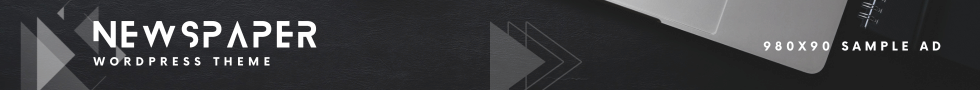

What happens to knowledge when it isn’t written down but carried instead through songs, recitations, and dance? This question prompted a journey across Africa, where oral storytelling, festivals, and music form more than mere entertainment—together, they are a living archive of history, identity, and continuity.

In the Mande regions of Mali, Senegal, and Guinea, the griot (or jeli) tradition flourishes amid rapid modern change. Griots serve as historians, musicians, and custodians of genealogies, holding centuries of lineage in the chords of a kora (a 21-stringed instrument) or the melody of a balafon. Each performance not only preserves political history and moral teachings but also adapts to shifting contexts, demonstrating that oral traditions remain remarkably nimble—even in the digital age. Far from simply recounting the past, griots actively shape it, weaving contemporary references into their narratives and ensuring younger generations never lose sight of their roots.

Further south, across southwestern Nigeria and parts of Benin, the Yoruba people uphold a deep oral tradition underscored by the talking drum. At its heart lies oríkì (praise poetry), dedicated to individuals, deities, or entire communities. Cultural custodians emphasize that oríkì is no vanity piece—it is an affirmation of identity that links today’s Yoruba population to ancestral legacies. Annual gatherings, such as the Osun-Osogbo festival, spotlight these traditions, with storytellers and drummers synchronizing praise poetry to communal rituals that reinforce collective memory.

Moving east to southeastern Nigeria uncovers a rich tapestry of Igbo oral tradition. Nightly storytelling, known as akụkọ ifo, addresses everything from heroic folklore to cautionary tales of greed and betrayal. These narratives also surface prominently during the New Yam Festival (Iri Ji), a seasonal event marked by masquerades, drumming, and communal feasting. Crucially, Igbo storytelling pervades daily life, imparting values like respect for elders and communal responsibility—not just during formal celebrations.

In South Africa’s Zulu regions, the izibongo (praise poetry) tradition has long been used to honour leaders and commemorate major events. Once reserved for royal courts and ceremonies, izibongo now appears in coming-of-age rituals, political gatherings, and even modern public celebrations. Local experts describe it as a rallying cry, transforming historical memory into calls for unity or social change. This evolution highlights how oral traditions remain deeply connected to present realities, shifting to include political figures or modern icons and thereby reflecting a living culture in motion.

Amid the Great Rift Valley, the semi-nomadic Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania anchor their oral traditions in respect for land, livestock, and celestial markers. Festivals—from weddings to coming-of-age rites—feature the adumu (jumping dance), each leap underscoring group identity and social harmony. Yet these customs also respond to modern pressures. As climate change alters grazing routes, storytellers adapt their narratives, ensuring that ancestral wisdom remains an active guide for new challenges rather than a relic of a bygone era.

In Ghana’s forested regions, the Ashanti/Akan people reveal another layer of African oral heritage. Their famed Anansi stories—often mischievous, sometimes humorous—carry moral lessons for audiences of all ages. Royal ceremonies such as Akwasidae weave drumming, regalia, and music into these tales, forming a vibrant communal narrative. While steeped in history, these festivals also function in real time, reaffirming political ties and re-examining moral codes for each generation.

Throughout Africa—whether at Swahili poetry gatherings on the eastern coast or among Tuareg music traditions in the Sahara—oral storytelling anchors community life. It raises a crucial question: How do such knowledge systems endure when society increasingly relies on written and digital records?

The conclusion from these travels is that oral traditions are anything but static. They evolve in response to technology, urban migration, and global developments such as climate change or political shifts. Rather than fading, they absorb and reframe these influences, creating a responsive guide to contemporary life without abandoning deeply rooted identities.

From the Mande plains to Lagos’s bustling streets, from Igboland’s fields to the Ashanti’s festivals, Africa’s oral traditions constitute a living tapestry of history and identity. The griot may stand as the earliest emblem of this heritage, but it persists in every chant, mythic narrative, and festival across the continent. By following these footprints—whether in praise poems or new forms of creative expression—we find that oral traditions are more than historical archives; they are dynamic tools for navigating the future, ensuring the conversation between ancestors and descendants never truly ends.